40 yrs ago: "Tempest" by EM entered the Memphis Brooks Museum of Art

40 years ago this week, Tempest a painting by Elizabeth Murray, entered the collection of the Memphis Brooks Memorial Art Gallery. On February 14, 1981, the local paper published this article by Donald La Badie titled This Stormy Piece of Art, No ‘Tempest’ a Teapot.

Elizabeth Murray (1940-2007) Tempest, 1979, Oil on canvas, 120 x 170 in. (304.8 x 431.8 cm) Collection of the Memphis Brooks Museum of Art, Memphis, TN. Gift of Art Today, purchased with matching funds from the National Endowment for the Arts (80.7). © The Murray-Holman Family Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

This Stormy Piece Of Art No ‘Tempest' In A Teapot

By Donald La Badie

February 14, 1981

Commercial Appeal, Memphis, TN, p. 9

On Sunday, Feb. 22, Art Today's 1980 gift to Brooks Memorial Art Gallery will be unveiled at the gallery.

The two works that make up this year's gift are Alan Shields' Cat Nip Tabs, a work of acrylic and thread on unstretched canvas, and Elizabeth Murray's oil on shaped canvas, Tempest.

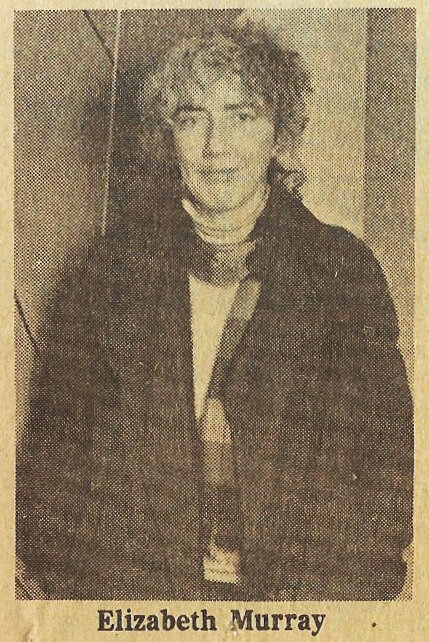

While in town this week for a visit to repair a crack in the surface of her painting, Miss Murray discussed the work, the art that led up to it and her background.

Titles are sometimes meaningless in a work of art. In the case of Tempest, it could not be more apt. Inspired by Giorgioni's "The Tempest, it suggests a storm system moving through space.

Tempest gives off a feeling of extraordinary energy, of movement within and without. A central conflict is created within to the point that a viewer feels the painting might break apart at the center, its halves moving off in opposite directions. At the same time, the whole painting creates the illusion of inching across the wall on which it is hung.

Miss Murray distrusts the manner in which terms like "abstract" are thrown about, and rightly so. However, in the last decade she has been generally regarded as an abstract painter. And it would be difficult to think of another, more appropriate term for her work.

She was one of those persons with precocious talents in art as a child. In high school, her ability won her a scholarship at the Art Institute of Chicago. "I'd had the idea I wanted to be a commercial artist, but after I was exposed to the masterworks there, I was overwhelmed and decided somehow I didn't want to do that. I can understand the problems some people have with modern art. My God, the energy of Giotto. And on a more ordinary level, it didn't take me long to find out that I preferred the people in fine arts to those who were in fashion and advertising.

"I took figure painting at the Institute, but it bored me. I have a lot of respect for good realist art, but I wasn't interested in painting what was there. When I tried painting, I felt I couldn't paint at all. I felt confused, afraid and always on the brink of failure… At whatever level you start, you really want that something you do to be the best."

Miss Murray received her MFA from Mills College in Oakland, Calif., and continued painting. In 1972, she sent slides of her work as a first step for entry in a Whitney of American Art annual. To her surprise, Marcia Tucker, then a curator at the Whitney with a sharp eye for new talents, accepted her paintings.

On first seeing Tempest, one has the impression that the 40-year-old Miss Murray has been involved with sculpture, an impression not far off the mark.

“I've never been a sculptor," she said last week, "but I've felt very close to sculpture and there was a period when I came near to crossing over. Between 1965 and 1970, I became involved with the three-dimensional to the point where my paintings went right off the wall and into space. The flat surface seemed too limited to me at that point.

'That was a necessary venture, and I see my students at the School of Visual Arts attempting to extend painting in the same manner. For a long time now, of course, a lot of artists and critics have been saying that painting is dead, that it isn't hip, so artists search for other ways.

"In the early 70s, I became very tied up with images, and then a very basic change began to take place. I started to try to get rid of the representational elements in my work - to purify, to simplify, to modify, to get rid of my ego. Color became very important and I became involved with all kinds of shapes and I found that the shapes within my paintings led to the external shapes.

Giorgione (1477/78-1510) “The Tempest,” (1506-1508, Oil on canvas, 33 x 29 in. Collection Gallerie dell’Accademica, Venice

"I was thinking of Giorgioni's The Tempest when I did my Tempest. I wanted the painting to be real clear and clunky. And there's no way you could work with a big six-pointed shape without being clunky.''

Tempest has what the artist calls a "twin painting" which was purchased by the St. Louis Museum. This is the work borrowed by the Whitney for the 1981 biennial, and admired by [Hilton] Kramer.

“That one is vertical rather than horizontal," she pointed out. "It's called 'Writer.' I was thinking of the way in which painters and sculptors and writers are different from other artists like actors. We all share an isolation. When you're really working, you're there all by yourself."